October 29, 2021

Tracking A Treasure: Tagging Endangered Sea Turtles in Belize

BY: Martinique Fabro

Written by: Carolee Chanona

The grandeur of instinct.

Unfettered by the world around it—of smart phones, curious onlookers, and even excited ripples of footsteps in the soft sand—instinct alone led this critically endangered turtle ashore to Gales Point Manatee. Here, dedicated efforts to preserve hawksbill turtles has been almost a two decade-long plight, thanks to Hawksbill Hope.

“Did you eat? I’m picking you up in 5 minutes. We need to leave now if we want to be there when she’s back.”

The line clicks to silence. Who is she? Leave to go where? Back from what? Sure as rain, I had all my questions indulged 5 minutes later—with answers just in time for the intersection into the Coastal Road.

Formerly a homesite for pre-colonial loggers, Gales Point Manatee is a village on a peninsula in the Southern Lagoon, roughly 2 miles west of the coast. Today, it’s mostly Creole residents are farmers and fish with a culture of conservation so tightly woven into the fabric of this place; after all, it is impossible to separate the importance of this delicate habitat from the very ones reliant on it, who have spared no effort to preserve it. And with the largest turtle nesting beach for Belize with the highest frequency of (critically endangered) nesting Hawksbill in the Caribbean, protecting these beacons of hope should come as no surprise.

Identifiable by their falcon-like beak with a pointed and sharp edge, the critically endangered Hawksbill sea turtles thrive on these soft, sandy terrains tucked away from mass development. It’s on this stretch during nesting season that Kevin Andrewin of the non-profit organization Hawksbill Hope patrols, monitors, and—when luck smiles on him—tags female sea turtles who come ashore to nest.

I watched the calm, emerald lagoon roll in on both sides as the Coastal Road gave way to a single dirt road onto the peninsula. One way in, one way out. Picking up Kadia, Kevin’s daughter who led the way, we headed straight back out to the coast. The adrenaline threw me into my memories of 2014, when I was but an innocent bystander: walking the beach of Half Moon Caye, I serendipitously stumbled upon a nesting female halfway through her process. With each complete range of motion, she sank deeper into the cool, soft sand of Belize’s easternmost territory to lay. Breathless, I ran to tell the others while the ranger waited eagerly for her to begin, so that she could record details like her species, length, and width without disrupting. Demarcating the nest, the rangers keep a close eye over the next 2 months; here in Gales Point Manatee, Kevin does the same. Except this time, we’ll be tagging this female with a real-time tracking satellite.

And with his adult years actively involved in the conservation of Belize’s three endangered sea turtle species and Antilliean manatees, Kevin will tell you. “I knew early on that this—being hands-on in the dirt—is what I was meant to do.” But as they say, it takes a village, and that village is Gales Point. The Gales Point Manatee Sanctuary has twenty two ecosystems identified in the area under the UNESCO classification system – twenty terrestrial ecosystems and two aquatic systems.

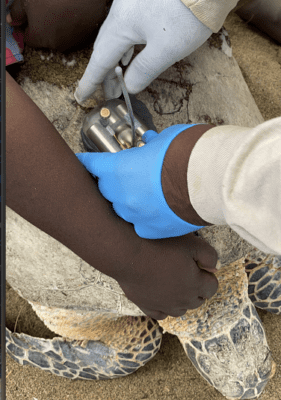

Kadia jumped out, and we followed quickly behind to meet Kevin, alongside her brother and her mom as if they’ve done this 40 times before, which they likely have. Working like a well-oiled machine, his son held onto the female turtle while Kevin warmed up the marine putty between the palms of his hand; Kadia and her mom worked just feet away to start synching the satellite tag and turtle insert.

“Can you switch with Kelvin? He’s getting tired. Just hold onto her shell while we prep the epoxy.”

I didn’t think twice, and quickly switched over. The turtle was calm and I tried to do the same while getting comfortable as my legs made a V in the sand behind her. Not that I could say it, but my biceps started burning first. She’s neither small nor weak; Hawksbills grow up to about 45 inches in shell length and 150 pounds in weight.

Thankfully, Kevin moved quickly: sanding down her shell, carefully securing the transmitter on the cleaned area, and talking through how the real-time data transmits. While stirring up the marine-based epoxy, Kevin spoke about Hawksbill Hope. Founded in 2009 as a non-profit by Dr. Todd Rimkus of Marymount University, Hawksbill Hope provides support to this sea turtle tracking program, paying for supplies and the wages of Belizean locals like Kevin who monitor these nesting beaches. Through the nesting season, a female hawksbill turtle will lay some 90 to 110 eggs. Per season, turtles can produce up to seven nests June through November.

As a road-map for those involved in sea turtle conservation, satellite telemetry answers key questions for conservation planning—like where these sea turtles go after leaving the beaches of Gales Point Manatee. Designed to be harmless and to fall off after a few years, the real-time data will tell researchers where important feeding areas are, offer insight into migration patterns, and help anticipate where turtles may come in contact with fisheries and their gear.

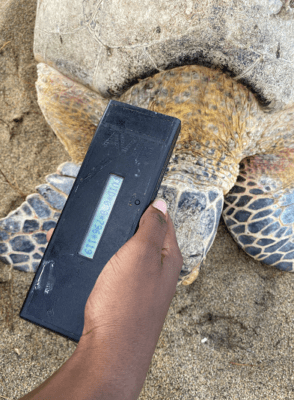

But, what was being immortalized was not the athleticism of Kevin capturing and tagging so much as the role these turtles played in uplifting the community of Gales point, in sharing enthusiasm for the conservation effort with all the others actively involved. It was exhausting and exhilarating at once, but no matter how tired I got, I never wanted to stop holding her. Here, with my heels wedged in the sand as we both faced the sea, I watched the epoxy dry onto the electronic device, no bigger than a billfold wallet, remotely transmitting information that enables the turtle to be geolocated by satellite as soon as it touches water. Turtles face threats from climate change, destructive fishing gears, but most importantly, from the loss of their nesting and feeding grounds. Protecting vital nesting grounds like Gales Point Manatee is crucial to their survival, considering that each nest has less than a 5% survival rate in the wild.

The sea’s infinite power, like a sea monster’s flanks panting, seems to carry us gently through the story of this female sea turtle, coming ashore on this random Sunday afternoon in September.

“Alright Carolee, you held her, so you get naming privileges. I need to record it before we let her go, and it’s almost time.”

I gaze down and the choice is easy. Tesoro. A term of endearment—evocative, emotional, and passionately fitting of every conservationist I’ve met before me—for the people, things and moments we treasure. It’s one of the small tattoos on my left hand, and a stark reminder as I hold her: The Hawksbills of Belize must be treasured, and it’s up to us. I treasure catching a glimpse behind the veils of a place like Gales Point Manatee, to see the efforts of residents like Kevin and the community behind him to make a path for these sea turtles to call home when they’re not at sea.

Kevin repeats after me. Tesoro. And each time she surfaces for air, Tesoro’s transmitter will ping.

I emerge shaky with pride and thrill after holding all the tension in my arms. It’s a very Belizean experience: the unprepossessing turning into the sublime, just as the half-paved road gave way to this lingering stretch of delicate, brown-sugar-like coastline; the same way the mess of sticky epoxy gave way to a state-of-the-art, $5,000 USD transmitter tag that’ll carve out one Hawskbill’s path on a computer screen. The simplicity of each ping has now become a theatre of wonder and conservation.

I gently released my hands from the front of Tesoro’s shell and she paused, only briefly, as if she could smell the ocean. Kevin cleared a path ahead of her, and everyone who came out for a Sunday swim cheered her on. From behind, I watched Tesoro sink into the frothy, warm ocean ahead of her with each shimmying flutter of her fins. Hope and concern held in momentary balance before Tesoro plunged out of sight. I follow behind her soft indents in the sand and hear Kevin say, “Until next time,” sighing with pleasure and gratitude.